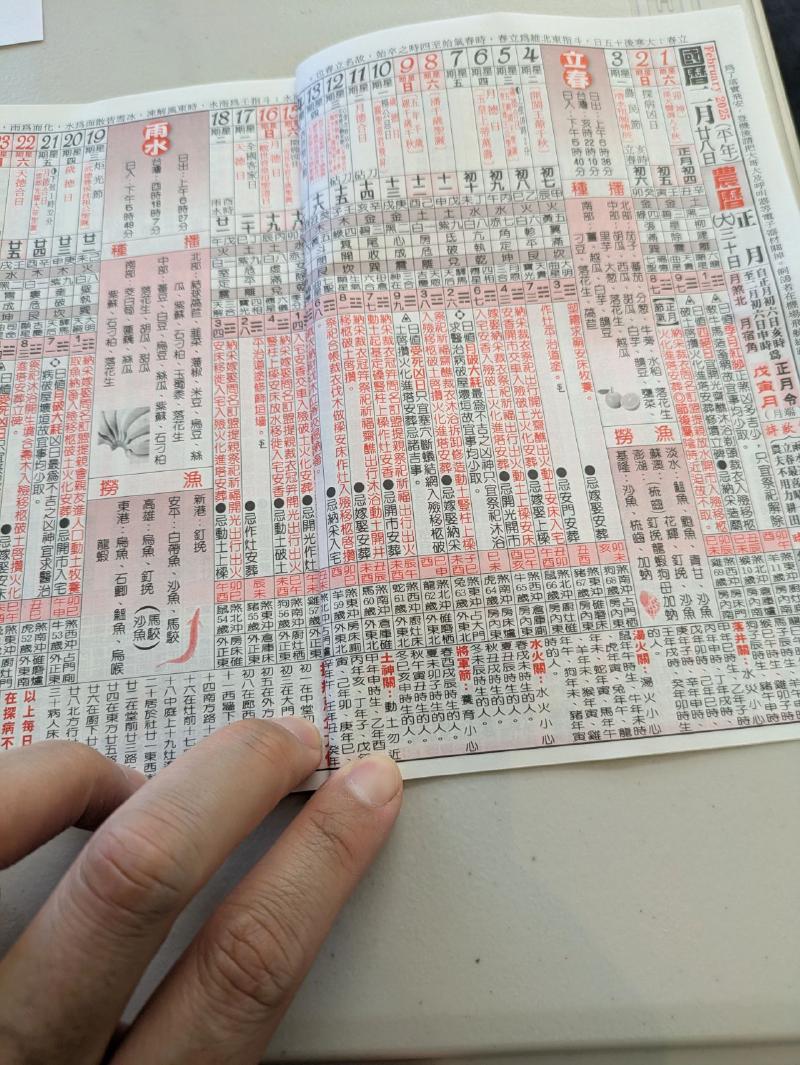

The Chinese almanac (通書/農民曆) might be the world’s oldest continuously published data science project.

Imagine farmers across generations—not just recording when to plant, but meticulously noting correlations between celestial patterns, weather changes, and successful harvests. They weren’t guessing. They were building a prediction engine using the only tools they had: observation, documentation, and pattern recognition.

Dating back to around 2500 BCE during the Xia Dynasty, these almanacs began as fundamental agricultural guides. But they were never static. Each generation added layers of insight, correlating moon phases with tides, star positions with seasonal changes, and weather patterns with optimal planting times.

What makes this remarkable? They didn’t have the why. Ancient farmers couldn’t explain gravitational relationships or atmospheric science—they simply noticed what worked, documented it, refined it through trial and error, and passed it forward.

This wasn’t superstition. It was an empirical method before the scientific method existed.

The modern Chinese almanac evolved to include predictions for nearly everything: auspicious days for marriages, business ventures, travel, construction. It became a cultural algorithm—a complex system trying to predict outcomes based on observed patterns.

Sound familiar?

AI models function precisely on this principle. They don’t understand causality in the way humans conceptualize it. They observe patterns in vast datasets, identify correlations, and make predictions.

GPT doesn’t “understand” language any more than ancient almanac creators “understood” astrophysics. Both systems recognize patterns that produce reliable outcomes without necessarily grasping the underlying mechanisms.

The difference is scale and speed. Where almanac creators needed generations to refine their models, modern AI can process billions of examples in days.

But the philosophical approach remains strikingly similar: notice what works, document the patterns, refine through iteration.

Perhaps what’s most profound is that both systems—separated by four millennia—reveal something essential about human knowledge acquisition. We often recognize useful patterns long before we understand why they work.

The question isn’t whether we should trust pattern recognition without complete understanding—we’ve been doing it successfully for thousands of years. The question is how we incorporate these powerful pattern-recognition tools into systems that serve human flourishing.

The ancient almanac makers would recognize our modern AI endeavors instantly. They were, after all, in the same business: turning observation into prediction, and prediction into wisdom.